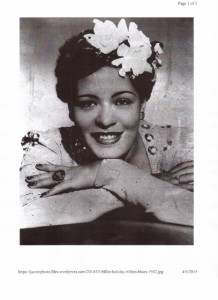

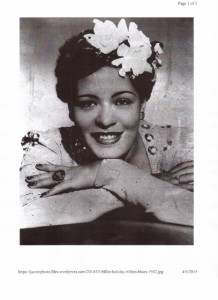

Billie Holiday

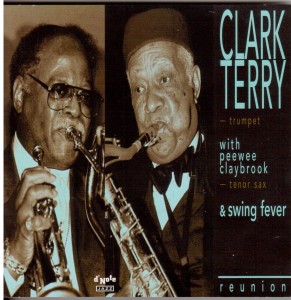

Billie Holiday Swing Fever is celebrating Billie Holiday’s birthday with their show at the Panama Hotel, in San Rafael California, on April 7th, 20015; as we have done for many years.

Billie Holiday may be the finest singer jazz has produced. She is surely the most legendary. Her recordings with Teddy Wilson’s studio groups in the mid-1930s startled the jazz world and brought her attention that rarely faded until her early death in 1959 at age 44. Her problems with men and dope brought notoriety along with fame. That became part of the legend too. The recordings made in her declining years continue to fascinate fans sixty years later, a fascination that sometimes approaches necrophilia, as Billie became known as not only jazz’s greatest singer, but also its most publicized victim. In the early recordings her songs are, for the most part, fresh and hopeful. Later the songs reflect mistreatment, self-sacrifice and her failing voice reflects a hopeless grinding downhill journey. Every one of us knew where it would all end. Her death (she was arrested for narcotics addiction on her death bed), resulting from her problems and at a relatively young age, was the capper, stamping her legend in bronze.

And still there is the music. Billie’s forte was not the Blues, as popularly supposed, but the standard American popular song, and how she could enhance, imbue and transform the best and even the most trivial of these songs still brings a thrill to both ear and heart; at least my ear and heart.

Our Billie birthday tributes give the band a chance to crack out many of the songs that she sang so beautifully. Most of them, such as “Foolin’ Myself,” “This Year’s Kisses,” “I’ll Never Be the Same,” have dropped almost completely from sight. The easy conclusion is that the songs didn’t last because they didn’t stand up as quality songs, but that’s far from the truth in the case of the three that I just mentioned, or for many others.

Billie Holiday started to catch the attention of the jazz listening public with those early Teddy Wilson recordings. In 1936 she was a distinctly new experience. She did not possess a large voice or have a large range. She, like Bing Crosby before her, was perfectly matched to the new development, the microphone, which was merciful to smaller voices and introduced intimacy. Al Jolson and Bessie Smith had to project to the back row of a theatre to be heard. Suddenly singers were singing in natural voice. Billie was also absorbing the lessons of Louis Armstrong and, more directly, the tenor saxophonist Lester Young, and the result was fresh improvisation and phrasing. Not always to the composer’s satisfaction, Billie bent melodies to make them right for her. In some cases this was driven by her lack of range. The Cole Porter song “Easy to Love” stands out. The melody went beyond her comfortable range and to avoid the problem, Billie never sang the composed melody, but simulated it, ducked the highest and lowest notes, and put the emphasis on expressing its lyrics and making it swing. She did the same with many songs, whether in her range or not

My favorite Billie Holiday is the many records made in the mid-30s under the direction of pianist Teddy Wilson as leader. Those records were some of the early thrills for me, all the more so because of wonderful solos by Bunny Berigan, Lester Young and the rest of the pickup groups, glued together by Hammond and Wilson. I listen to them now and the same thrills return, as well as new ones. The old story passed around for years, is that a lot of sappy pop tunes were thrust upon Billie in the early years, and that the only dignity brought to this ephemeral commercial pabulum was Billie’s singing. It’s true, some of these songs, as songs, were genuine forgettables. In some cases they were dashed off by a few pop writers and were never intended to survive more than a day. A few of the songs were already standards (“Love Me or Leave Me,” “Summertime,” “Am I Blue”) or became standards through outstanding band recordings or by Broadway musicals, or when vocalists like Crosby and Sinatra bullied them into prominence. And then there was a third kind, the many more songs that deserved to survive and didn’t. Whatever became of “Easy Living,” for instance, or “I Hear Music”? Some songs like these never became hits, or if they were hits for a moment you didn’t hear them two or three or five years later.

In the 1940s the quality of Billie’s songs grew as her singing and popularity ripened. The songs were also more doleful, reflecting the blue side of love and life, and one, “Strange Fruit” starkly political. And then came the decline, the sound of brake shoes digging into the drums.

Billie Holiday died at 44, her career spanning a scant 25 years. Jazz is famous for short careers. Think of Nat King Cole, Bunny Berigan, Chu Berry, Bix Beiderbecke, Charlie Parker. But compare Billie’s with the long careers of, say, Big Crosby, Frank Sinatra (more than 50 years), or Tony Bennett, still singing in his 80s, and Herb Jeffries, in good voice at 96. Nearly all of Billie’s 25 years were, for both music and lifestyle reasons in the spotlight. Some of it, most of it, is great music. But for me, none of it recaptures the freshness of her early songs and those eternally precious Teddy Wilson recordings where “Ooo, Oo, Oo, What a Little Moonlight Can Do” could become a classic.